Permanent Damage

Because our government and employers failed to protect nurses, thousands of us will struggle to live with Long Covid for the rest of our lives, jeopardizing our livelihoods and careers.

By Rachel Berger

National Nurse magazine - July | August | September 2024 Issue

When Shoharab Chaudhary came to the U.S. from Nepal in 2010 at 22, he came with one goal in mind, to be a nurse.

“When I was in high school I didn’t know what I was going to do, so I started volunteering at [our local children’s hospital],” said Chaudhary. Initially he thought he might want to be a doctor, but he quickly changed his mind. “I was really inspired to become a nurse, because as a nurse you get to be closer to the patient and get to spend more time with them.”

But in Nepal at the time, only women were allowed into nursing school. So when Chaudhary got the opportunity to come to the United States, he didn’t hesitate. He graduated from nursing school in 2015 and began working at UC Davis Medical Center in 2016.

“It was a dream come true,” recalled Chaudhary. “As a nursing student, I completed a lot of my clinical hours at UC Davis and had always imagined myself working there.”

Today Chaudhary still works at UC Davis, but he is no longer caring for patients. He suffers from more than 70 debilitating symptoms including brain fog, dizziness, heart palpitations, and fatigue — all associated with Long Covid, an illness he contracted on the job.

“It is heartbreaking,” said Chaudhary. “I love bedside nursing and now I am a hospital operator [for the communications system]. I don’t even know how long I will be able to do this.”

Unfortunately, Chaudhary is just one of millions of people who are living with the debilitating effects of Long Covid. In June of 2024, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 5.5 percent of all adults in the United States — which translates to some 14 million people — reported they were experiencing symptoms from Long Covid.

“Since the emergence of Covid we have seen far too many nurses pay the price for the CDC’s refusal to insist on following the precautionary principle,” said Jane Thomason, National Nurses United’s (NNU) lead industrial hygienist. “This has resulted in an enormous number of avoidable Covid infections and tragic deaths among health care workers. Today we see many people struggling to live with Long Covid.” Without proper protections and precautions, nurses are more likely to be exposed at work to a disease that increases their likelihood of losing their whole livelihood and profession.

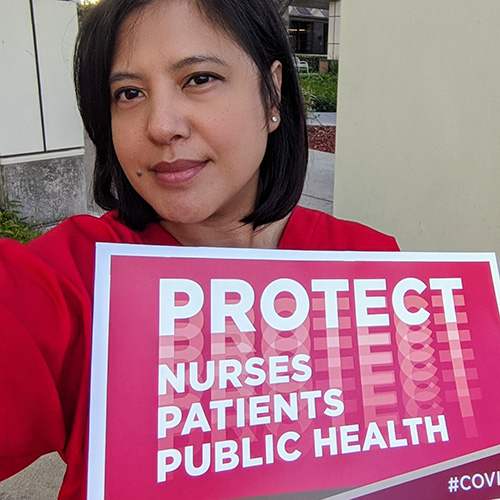

NNU has always argued that the first line of defense against Long Covid is prevention of Covid infection by ensuring that nurses and patients are protected. That is why since the start of the Covid pandemic, NNU has been advocating tirelessly for a strong national infectious diseases standard coupled with robust enforcement.

But throughout the pandemic and even now, our workplaces are not taking proper precautions.

To help illustrate the need for such protections and to better understand what is happening right now in hospitals across the country, NNU surveyed nurses from across the country on infectious disease measures in their facilities in March and April of 2024.

“This survey of 775 nurses from 45 states and Washington, D.C. shows us in stark detail how hospitals are failing to provide essential elements of infection prevention, including patient screening, isolation of infected or potentially infectious patients, or provide the necessary personal protective equipment to health care workers,” said Thomason.

The survey found that one in six nurses reported that patients in their facilities were never screened for infectious diseases. A majority of nurses report inconsistent isolation of patients who have or might have a respiratory infectious disease. Inadequate screening and isolation of infectious/potentially infectious patients puts health care workers, patients, and visitors at increased risk of exposure to infection with respiratory infectious diseases.

In January 2024, NNU conducted a nationwide survey asking more specifically about Long Covid experiences among the 2,600 registered nurse respondents.

The survey found that many nurses reported experiencing Long Covid symptoms that impacted their work or daily life. Nearly 70 percent of nurses who responded reported they had been diagnosed with Covid at least once. Of those nurses, more than 53 percent said their Long Covid symptoms have affected their ability to work, and more than 65 percent of those nurses who’ve been diagnosed with Covid said their Long Covid symptoms have impacted their daily activities outside of work.

Though NNU successfully won an emergency temporary standard on Covid-19 for health care workers in June 2021, the first emergency standard issued by the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) since 1983, OSHA has yet to make the standard permanent. NNU is unrelenting in pushing OSHA to create a permanent standard not only limited to Covid-19, but covering all infectious diseases, and is now circulating a petition collecting signatures to do just that.

Chaudhary’s struggle to reorganize his life after his Long Covid diagnosis is a clear example of what is at stake when nurses are not protected from infectious disease on the job.

Very early in the pandemic, in March 2020, Chaudhary was working as a charge nurse in the ICU when he became ill with what he believes was Covid. However, because his symptoms didn’t match the understood profile of Covid at the time, he was not able to get tested for Covid.

“I had fever for almost a week and a half and a cough that wouldn’t go away,” said Chaudhary. He said the cough was so intense that it was impossible for him to lie down. “I had all these gastrointestinal symptoms, muscle aches, and like sore throat that wouldn't go away.”

“There are many barriers to getting a Long Covid diagnosis,” said Rocelyn de Leon-Minch, an industrial hygienist with NNU. “For those who were infected early in the pandemic, they may not have a positive test that shows their infection, as testing was severely limited. In addition, the majority of Long Covid cases are in people who had a mild or asymptomatic infection, who may not have taken a Covid test or tie their symptoms with Long Covid.”

In the best of cases, getting care for Long Covid is difficult. But not having a test that links your symptoms to Covid, makes it even more difficult. One study found that an estimated 70 percent of Long Covid clinics in the United States only accept patients with a prior positive Covid test.

Chaudhary said that despite his debilitating symptoms, he worried about how he would get health care or insurance if he were to leave his job. So he kept working after his first infection and second infections, even as he felt his health deteriorating dramatically.

“After the second Covid, I couldn't even sit up,” recalled Chaudhary. “As I sat up, even in a chair, both my arms would just go limp and weak. My family was feeding me for a week.”

When he was able to work, he struggled to manage multiple symptoms including fatigue, jaw pain, body aches, persistent GI problems, and tachycardia.

“My heart rate would be like 170. My patients, they are admitted with 120, 130, 140 and I'm taking care of them with 170. And I did that for a year. I felt I was getting worse every single day, but I was scared of losing my insurance if I left work.”

Nurses and other health care workers are at an increased risk for Covid-19 infection due to the nature of their work and repeated exposure. Chaudhary believes he was infected with Covid at least three times.

“Unless you have it, you don’t really understand,” said Mirasol Streams, a registered nurse at Emanate Health Inter-Community Hospital in Covina, Calif. Streams contracted Covid in December 2020 while caring for a Covid-positive patient on a BiPAP machine.

After testing positive, she feared for her family’s well-being so she spent four weeks in a hotel. “During my stay it was hard to take a shower, I was dizzy all the time, I felt like I was blacking out.”

Streams was never hospitalized and tried to go back to work after her initial illness. “My first night, I was a sitter for a traumatic brain injury patient, and this person was so confused, I had to run after him. But I was exhausted, I couldn’t do it.”

She tried to continue working for several months on light duty, but that too proved too exhausting for her.

“It attacked me from head to toe,” she said, listing off just some of her many symptoms. “I have brain fog, I have shortness of breath, tachycardia, GI bleed.”

When she first went to a workers’ compensation doctor, she said they were ill-prepared to deal with her case. “I think they were used to dealing with physical injuries,” she recalled. “They didn’t even take an x-ray. The care was very substandard.”

Chaudhary had his own issues with workers’ compensation and trouble finding appropriate care. He said because he had no preexisting conditions prior to getting Covid, when symptoms arise, his primary care provider says they are unable to see him, and he should be seen by his workers’ compensation physician. But workers’ compensation doctors don’t have an understanding of Long Covid.

“That’s been another challenge: to find a doctor consistently,” said Chaudhary. At one point he was referred to a clinic in Los Angeles to get Long Covid care. Yet he was living in the Sacramento area, some 385 miles away. Too weak to drive himself, Chaudhary had to find someone to drive him down and back every two weeks so he could get care.

Both Streams and Chaudhary say they are angry that their government and their employers failed to protect them when they were caring for their patients.

“I was mad at everybody,” said Streams. “I was mad at the government for not stockpiling PPE, when we had plenty of warning about all of this. I was mad at the CDC who kept fighting the nurses saying it’s not airborne. They kept saying it’s not airborne, you’re fine. You’re fine with a bandana, you can reuse a mask.”

“This was all preventable, if we had the appropriate PPE,” lamented Chaudhary. Because he was working as a charge nurse and did not have a patient assignment, hospital management refused to give him an N95 respirator. “But then we were short staffed, [and] staff were having Covid at the time and they were calling in sick. So if they needed any kind of help in any of the isolation rooms, they were [calling for the] charge nurse. So I was going into each and every room without anything.”

By NNU’s count, by August 2023, 501 nurses in the United States had died from Covid-19. Among the dead was Amelia Agbigay Baclig, a 63-year-old nurse known affectionately as “Mama Amy” who worked beside Streams.

“She was very concerned about getting Covid because she was working on the Covid floor,” said Streams. “So I and some other coworkers would volunteer if it was her turn [to work on the Covid unit.] People would switch with her so that she didn't have to.”

Streams said Baclig’s death was devastating. Nurses were heartbroken that although Baclig had worked at Emanate for decades, the hospital refused to admit her to the hospital’s ICU even as her family and coworkers wanted her there.

“She would have been taken care of by those who loved her and she would not have been alone and passing away with strangers,” said Streams, fighting back tears.

Currently, the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) is updating the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Isolation Precautions guidance, which shapes infection control and prevention practices in hospitals, nursing homes, and other health care settings across the nation and around the world.

“For too long, HICPAC’s proposals have ignored critical science and weakened current protections for health care workers and patients because they have been dominated by infection prevention and industry viewpoints, to the exclusion of other essential expertise,” said Nancy Hagans, RN and NNU president.

After a robust campaign, NNU achieved a remarkable victory this year, when two members of the NNU staff were invited to add their expertise to the CDC process.

Thomason has been invited to join the HICPAC workgroup and Lisa Baum, lead occupational safety and health representative at NNU affiliate New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA), has also been invited to join HICPAC.

“This is an essential step forward for HICPAC to include labor, occupational health, and industrial hygiene perspectives in the workgroup,” added Hagans. “Our expertise is essential to crafting robust, science-based guidance that fully protects health care workers and patients from infectious diseases.” NNU continues to advocate for improved transparency and engagement with frontline nurses and other health care workers.

For Streams and Chaudhary, their lives have changed dramatically since they became ill with Long Covid. Streams said her relationships have suffered because some people in her life have questioned why she has not been able to return to work. Her family’s finances have suffered too as they became dependent on workers’ compensation and then state disability insurance to help support the family of four.

It is now three years after her first infection, and Streams still does not leave her house often and she suffers from bouts of lethargy and depression.

“I’ve never had depression before until this,” said Streams. “There were times I just wanted to cry because just [the way] all the things are, the stress of it.”

Workers’ compensation initially approved therapy for Streams, but later denied the benefit. After fighting with the workers’ compensation for years, Streams has recently been approved for mental health treatment.

In March, she began taking naltrexone to combat her fatigue and brain fog. She said she has seen some improvements with the treatment as she sleeps better and her energy levels have improved.

With her state disability gone, Streams is hoping to go back to work soon. But she is concerned about what awaits her.

“I'm kind of scared because if there’s a new strain coming around again,” said Streams, “I don't know what to expect. I hope I remember what I need to do when I need to do it. I’m concerned about having brain fog, because a lot of being a nurse is teaching our patients and if I’m forgetting what the word is, I don't feel like I'm gonna sound like I know what I'm talking about.”

Chaudhary works light duty as a hospital operator. But he said he still deals with 10 to 20 Long Covid symptoms daily.

“My most severe symptom right now is dizziness,” said Chaudhary. “Even turning my head can get me dizzy. I get blurry vision every time and my ears start ringing. So it's like I'm totally blind and deaf when I start getting dizzy.”

He wants nurses and other health care workers to understand that Long Covid is a serious illness.

“A lot of people are not aware of how severe Long Covid can get,” he said. “They think it is a respiratory illness. But I see like four or five different specialists already and all of them know it's Covid, but they don't have any idea how to treat me or what to do. At this point, my doctors are just doing symptom management treatment for me.”

Streams and Chaudry are adamant: Nurses must do everything they can to protect themselves from infection by wearing an N95 or better respirator, getting vaccines, and taking the time to learn the proper way to don and doff their PPE.

“This is a novel disease,” said Streams. “The doctors will gas light you. Not everyone will believe you. You are a guinea pig with whatever medications they put you on. It’s very frustrating.”

Rachel Berger is a communications specialist with National Nurses United.