Caught in a TRAP

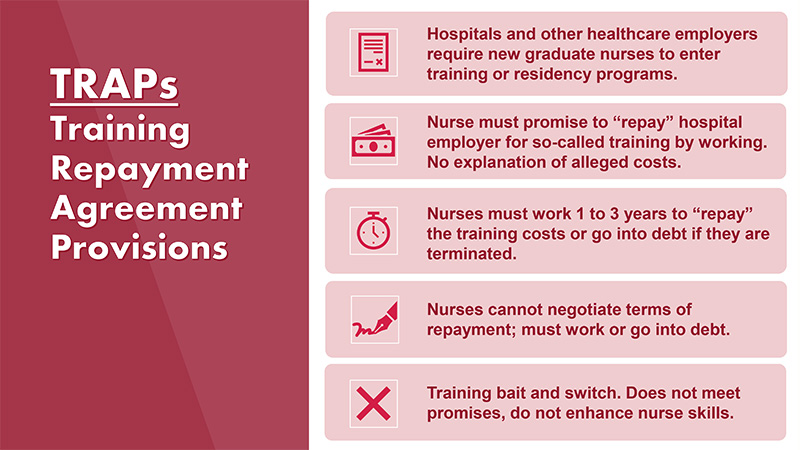

Hospitals are increasingly forcing new RNs to sign exploitative training repayment contracts to get hired. NNU is fighting back, on behalf of nurses, patients, and the profession.

By Rachel Berger

National Nurse Magazine - Oct | Nov | Dec 2022 Issue

Michelle Gaffney, an intensive care unit nurse, is not someone who is easily intimidated. She trained as an EMT, spent a few years as a livestock steward, has driven at midnight through Kansas snowstorms to help birth calves, and even tussled with a few bulls, including one who rolled her like a breadstick as he attempted an escape.

“I was standing between him and where he wanted to go,” Gaffney said, recalling the incident that left her “pretty banged up” and the doctor who reviewed her x-rays questioning her choice of employment.

But Gaffney said she did feel very intimidated by the constraints and threats that came with the contract she signed in order to get her first job as a nurse in Redding, Calif.

“Shasta Regional Medical Center was the only acute-care hospital at the time in town that hired new graduates with associate’s degrees in nursing,” said Gaffney. “Plus, I had spent years there working as a patient care tech, so I knew the caliber of the staff and I knew the hospital.”

Gaffney also knew from other nurses she would be required to sign a training repayment agreement provision (TRAP) when she took the job, but she didn’t know the details beyond that and management never took the time to explain it further. All she knew was the take-it-or-leave-it contract demanded she work three years, or pay $30,000.

Gaffney was already deeply in debt from nursing school loans and was caring for her disabled father whose dementia diagnosis required him to have 24-hour care.

“I felt like I really didn’t have a choice,” said Gaffney. “I needed a job.”

So Gaffney signed the contract.

While some form of employer driven debt schemes have existed for decades, they really began to proliferate and become widespread in the nursing field during the Great Recession, when some new grads had difficulty finding jobs and as hospital consolidation grew dramatically, said Carmen Comsti, a lead regulatory policy specialist at National Nurses United (NNU). Before that, hospitals took the opportunity during economic downturns to cut their education departments, discontinue preceptor and mentorship programs, and eliminate new nurse grad programs. New nurses used to receive 12 weeks or more of on-the-job preceptorship from an experienced RN before they took on their own patient assignments, and it was typical to pull a regular salary as a full-fledged staff nurse during that training and orientation period. Then hospitals started to force nurses into “residency” programs where nurses paid, either directly or indirectly through an affiliated nursing school, for that basic training and experience to transition into clinical practice. Now the hospital industry has gone a step further in insisting that nurses must pay exorbitant sums if they do not meet the terms of their hiring contracts, leaving them on the hook for thousands of dollars.

“These coercive agreements exploit the most vulnerable of our nurses, just as they are starting their professional nursing careers,” said NNU President Jean Ross, RN. “Hospital administrators have corrupted the notion of onboarding and on-the-job training by creating a scheme of modern-day indentured servitude.”

NNU and its affiliates have been working to eliminate these types of contracts, challenging their legality and denouncing them for holding nurses hostage as debtors.

In 2020, California Nurses Association successfully passed legislation, A.B. 2588, to bar employers from requiring direct care workers, including nurses, to pay for employer-mandated training. The bill also created retaliation protection for any job applicant who refuses to enter into a contract or agreement that binds them to paying for employer-required educational programs or training. Since then, CNA’s been working with California lawmakers to ensure this ban is enforced.

In addition, NNU has urged at the national level the Federal Trade Commision and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to investigate these exploitative contracts.

“TRAPs are just one way employers impose debt on nurses, but nurses can also incur employer-driven debt when hospital administrators demand that nurses repay sign-on bonuses if they do not remain at a hospital for the life of their contract,” said Comsti. “It is clear that employers are playing a whack-a-mole game as they create new ways to hide what is essentially indentured servitude. That is why we need government agencies to investigate and work with us to explicitly prohibit these schemes.”

At the urging of NNU and other union and consumer protection groups, the CFPB launched a workers’ initiative with particular interest in training repayment contracts.

In an effort to bring hard evidence of the harmful effects of TRAPs to the CFPB, NNU surveyed more than 1,100 union and non-union nurses about their experiences with employer-driven debt.

“The results of this survey show in stark and disturbing relief how these contracts negatively affect patient care by chilling a nurse’s ability to speak out about patient safety concerns or exploitative working conditions, and threatening retaliation for union activity,” said Comsti.

The survey showed that about a third of hospital RNs said they were in a TRAP at some point in their careers, usually in the beginning of their professional careers.

Jessica Ruth Day found her first job at a union hospital in Los Angeles County, but after she started working, she discovered she was not part of the bargaining unit because she was classified as an agency nurse. Concerned about patient safety, she wanted to speak to her union representative at the hospital, but was warned against it by her manager.

“I was told I would be in trouble if I talked to the union,” said Day. “I felt helpless. I felt like I just have to follow everything they say and I can’t have a voice.”

Day said her hospital was severely understaffed. New nurses were precepting even newer nurses. The turnover rate was extremely high and morale was very low. She could rarely take a break because the relief nurse would be caring for so many patients at once, she felt it wasn’t safe. One day when Day did take lunch, she came back to find one of her patients was taking her last breath.

“It broke my heart,” said Day. She felt terrible that her patient’s family was not called or by her side. The experience was so traumatic that Day never took lunch at that hospital again. “I would take a bite and then go watch my patients and then take a bite again. I found out that a lot of nurses were doing the same thing because it didn’t feel safe.”

This was a far cry from what Day had expected life as a nurse would be like. She’d decided to become a nurse at age 11 after she had to undergo surgery. “I was really scared,” said Day. But once hospitalized, she was awed by the nurses who reassured and cared for her. “I had the most amazing nurses who were so thoughtful. Ever since then, I wanted to be a nurse.”

Determined not to saddle herself with school loans or debt, Day had worked five years to save up enough money to attend nursing school.

When she graduated in 2018, her goal was to find a position in a hospital that offered a new graduate program. Like Gaffney, she found that with an associate’s degree, her opportunities were limited. So after she interviewed at an Inglewood hospital, she was ecstatic to get a text letting her know she’d gotten the job. She was told to go to an office in a nearby city to sign a contract.

“I was thrilled,” said Day. When she got to the office, she met a man who explained that Day would not be working for the hospital, rather for a staffing agency. He explained she would have to pay $15,000 for the training she would receive if she didn’t stay at the hospital for two years.

“He made it seem like the problem is new grads, like we are not reliable.” Day knew she was reliable and felt that signing the contract would show her new employers she was serious about the job, plus she was excited to get what she believed would be vital nursing training. “He was really very kind and reassuring. He really sold me on this dream that I am being taken care of and my career will be set.”

Day said she left the office feeling excited to start her first job as a hospital staff nurse.

“Obviously I knew it was going to be hard,” she said. She knew the work would be challenging as she was serving a severely under-resourced and often marginalized population. “I figured it was the population that would be the hard part and not the hospital, but it turned out to be the reverse.”

Comsti said as market consolidation in the health care industry has grown, NNU has seen hospital employers leverage their monopoly power to increasingly coerce nurses into debt through exploitative contracts. HCA, one of the largest health care corporations in the country, widely uses TRAPs when employing newly graduated nurses.

Kira Farrington is a single mother who grew up not far from the Great Smoky Mountains in North Carolina. At five she landed in the emergency room with a stomach bug, and was delighted when a nurse snuck her up to the roof to see the life flight helicopter.

“I never forgot how she made me feel as a person,” said Farrington. “I was like: ‘I am gonna be a nurse and I am going to do that for other people.’”

With some childcare help from her mother and by working as a certified nursing assistant, Farrington enrolled in community college for nursing school.

“I was living in income-based housing, driving a beat-up car, I had WIC, food stamps,” said Farrington. “Everything you can think of to get by.”

Farrington persevered, got her license in 2018, and took a job at HCA’s Mission Hospital in Asheville, N.C., the only hospital in her area where she felt she could get experience treating high-acuity patients.

“I was so excited to go to Mission,” said Farrington, “but that excitement was short-lived.”

As a condition of employment, Farrington knew she would take part in HCA’s StaRN program. But it wasn’t until she was signing her paperwork that she learned she would have to pay HCA $10,000 if she left before working at the hospital for two years.

“I was a little bit shocked and considered backing out,” she said, “But I thought, where else am I going to get this great training?”

What Farrington found was far from a meaningful training program. The first five weeks of the program was in a classroom and amounted to “a waste of time going over things we had already gone over in nursing school.”

Then for eight weeks she was precepted in the neurology unit. Later, when she did speak to union nurses, she found nurses who were transferred into ER from other units received 13 weeks of precepting in ER. “I was irritated,” she said, questioning how that was reasonable or fair to the new grads.

Gaffney too said she was shocked by the so-called training she received in her Redding hospital and blown away by the hefty price tag the hospital claimed it cost.

“It was not like they were sending us to Harvard,” Gaffney said. “The only thing I was offered was online training. I lobbied on my own to get physical classes because I was like, ‘Wait, you are telling me this costs $30,000 but you are barely giving me any classes at all.’”

Comsti points out that these hospital-run training programs are unaccredited and unregulated. She said TRAPs lure new nurses in “with the promise of enhanced training but what they provide varies widely. In essence it’s a bait and switch by hospitals, forcing nurses to pay for orientation and preceptorship that’s traditionally been viewed as part of the cost of doing business in the health care sector.”

Day said while she did find parts of her training program useful, she was surprised to find the program included newly hired experienced nurses. “It just seemed like this is the orientation for the hospital and it is not actually catered to the new grads, even though they were [claiming] that it was.”

Beyond the unfair and unnecessary financial liability for nurses, NNU is concerned that TRAPs effectively silence nurses from acting as advocates for themselves and their patients because they are afraid of jeopardizing their employment status.

In its survey, NNU found clear evidence tying TRAPs to poor working conditions. Of the more than 325 nurses surveyed who said they are or were in TRAPs, 34 percent said they felt restrained from complaining about unsafe staffing or other unsafe or unfair working conditions.

Farrington said during her first year, she kept her mouth shut about the terrible conditions at Mission. “I was afraid I would get fired and not have a job, I would not be able to get the income I needed. I was put in a position where I needed to just mind my own business so I didn’t lose my job.”

But as the months passed, Farrington said the poor conditions took a serious toll on her emotional health. She found herself crying as she drove the 45 minutes to work, crying at work, and sobbing on her drive home. “It got to the point where I would be driving and I would be like: ‘I could swerve my car and I wouldn’t have to go to work because I just knew it was going to be so bad when I got there,’” she recalled.

Then on Thanksgiving 2021, she hit her breaking point. She was caring for six patients at one time, including one who needed constant bladder irrigation and another who needed medication every 15 minutes for a brain bleed. After four hours, she had still not been able to see two patients, one who needed heart medication and the other who needed insulin. Desperate, she turned to a relief nurse for help only to learn another nurse was being pulled off the floor.

Incredulous, she protested. “I snapped,” said Farrington. But when an administrator overheard her complaints, Farrington was dressed down for airing her concerns at the nurses station.

The administrator told Farrington to go home, which further infuriated her. In the end, she felt the administrator was more concerned with silencing her than in making sure the patients were cared for appropriately.

For her part, Day said the poor conditions at her hospital led to deep moral injury as she watched the already under-resourced community suffer without appropriate care. Nurses were caring for too many patients and new grads were working without supervision in the ICU. “[The patients] need so much more help than what is being offered and I don’t think they deserve [anything less],” said Day. “Some people are scared to leave family members at this hospital. They have seen bad outcomes with other family members and are worried for their family members. I can’t tell them not to be.”

Day said there were so many codes and calls for a rapid response team at her hospital she started feeling like she was suffering from post traumatic stress disorder.

Eventually, her family contacted a lawyer about six months before Day’s contract was up. While the lawyer said there may be grounds to challenge the TRAP, he encouraged her to finish the contract term.

For Farrington, though, the psychic cost of continuing at Mission Hospital was just too high. Six months before her contract was up, she said she was unfairly let go, but did not want to fight to stay. While HCA has not come after her yet, the multibillion dollar chain has a history pursuing nurses. One nurse who worked at a Kansas HCA hospital was sued by a debt collection service even after he had set up a payment plan. Another nurse who left the same hospital before her contract ended received weekly letters demanding payment and was threatened with legal action. One nurse who paid HCA $6,000 after leaving a Florida hospital, said she believes she has been blacklisted from the chain.

NNU is calling on the CFPB to consider TRAPs and other employer-driven debt to be unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices under already existing federal consumer protection law. By regulating and investigating employers that use debt or the threat of debt as part of employment contracts, the CFPB can play a critical role in ensuring that nurses have safe and fair workplaces.

“It is a disgrace and a disservice to see hospital corporations extort and exploit a new generation of nurses,” said Ross. “We must welcome new grad nurses into the ranks by supporting and protecting them from the forces that seek to bleed them dry. The very health of the country is dependent on their commitment to the profession and their ability to advocate for safe patient practices.”

“I greatly appreciate the efforts of our union for shedding light on and pushing to end this coercive practice,” said Gaffney. “Nurse advocacy made TRAPs illegal in California and it should be the same nationwide. Nurses must be able to speak up freely without fear of retaliation or threat of financial devastation when patient safety is at risk. When nurses are silent, patients suffer."

Farrington said the burden of the TRAP, the pain of seeing her patients put in harm’s way, and the hospital administration’s complete disregard for her safety or that of her coworkers led her to contemplate leaving the profession.

“I was questioning, ‘Do I even want to be a nurse anymore?’” said Farrington. “For somebody who spent 27 years to become a nurse and wanting to do it for the reason of taking care of people because that is what you enjoy doing, and then getting put through this grinder. It’s like, ‘What have I gotten myself into?’”

Looking back at her experience as a new nurse, Day said she felt abandoned by an hospital administration that demanded she do the impossible, yet found fault with her if she failed to do what was demanded. “I had never been treated so terribly by an employer,” she said. “I didn’t feel like anyone was concerned about me, I was just there to fill a position.”

After seeking therapy to address the moral injury and PTSD she suffered, Day is now determined to speak out about her experiences. “I think a lot of nurses are afraid to speak up. But I don’t think that sharing the truth is ever wrong. I think it can be a powerful example and hopefully it can protect other nurses and make health care a better place.”

After leaving Mission, Farrington said there was no place near her home where she could get a position that would give her the experience in trauma care she needs to become a flight nurse. So she is packing up to move seven hours away from her family to work in a trauma center.

“I feel like I am being pushed out of the state,” she said, sharing her sadness at leaving her family, especially her mother and sister. While leaving her home state is painful, Farrington said a recent encounter with a former patient who thanked her for all she had done for their family in their hour of need restored her commitment to nursing.

“I cried like a baby in the hallway, because it meant so much to me,” said Farrington, breaking down in tears. “I was able to do something special for someone else in the worst times of their lives. I was able to bring a smile to their lives. That is what nursing is all about.”

Rachel Berger is a communications specialist at National Nurses United.