Blog

Nurses go on strike for proper gear, training to protect them against Ebola

It doesn’t seem like nurses are asking for too much as fears escalate over the spread of Ebola. They’re concerned about safety — not just for themselves but for their patients and for the public.

But hospital management hasn’t responded. Neither has Congress nor the president.

That’s why some 100,000 registered nurses and nurse practitioners across the country, including 400 at a Washington, D.C., hospital, are going on strike, picketing or holding rallies and candlelight vigils as part of a national “Day of Action” Wednesday to protest their lack of protective gear and training for taking care of Ebola patients. In California, 18,000 nurses will strike for two days, starting Tuesday morning.

“It’s a women’s issue,” says RoseAnn DeMoro, executive director of National Nurses United, or NNU, the nation’s largest nurses union, which represents 185,000 registered nurses. “If this were a [predominantly] male profession, the dialog would be different.”

You wouldn’t send a firefighter into a burning building or a soldier to war without the proper equipment, DeMoro and other nurses have said to me. Yet nurses don’t have the kind of equipment or the training they need to deal with Ebola — and potential Ebola — patients. In a survey by NNU of more than 3,000 nurses at more than 1,000 hospitals, 85 percent said that their facilities were not prepared to take care of Ebola patients and that nurses had not been trained adequately.

Strikes by nurses are legal as long as sufficient warning is given to the hospitals, where elective surgeries and procedures are rescheduled and “replacement” nurses are hired.

Nobody wants to go on strike, said registered nurse Megan Ottati, who’s worked at Providence Hospital in Washington for 18 months. “Unfortunately, it seems like the only way to get the attention of upper management at Providence on issues, especially safety,” she said. “You do what you have to do to ensure safety.”

Ottati is a telemetry nurse in a 22-bed unit for patients that have left the intensive care unit but are still being monitored closely. One nurse should have responsibility for four patients, she said, but too often there are only three, and sometimes just two, nurses sharing care for 22 patients. The thought of one of those patients having Ebola is almost overwhelming, considering the current staffing shortages.

“Ebola happens to be a microcosm of the bigger picture of the erosion of standards and conditions in patient care,” said Katy Roemer, a registered nurse for nearly 20 years who works at Kaiser-Permanente’s Oakland Medical Center in Oakland, Calif.

There’s been a dramatic shift in health care, explained DeMoro, as hospitals move from community-run enterprises to corporate institutions where the bottom line rules.

“Patients before profit — that’s what we believe in as nurses,” Roemer said. “What we see is profit before patients.”

Hospitals fail to maintain adequate staffing, compromising patient care while raking in “massive profits,” Roemer said. “But we aren’t given the resources to provide the standards of care we’re trained to…. It creates an impossible situation.”

“We’re tired of hearing, ‘We know what’s better for you than you do,’” from hospital management, DeMoro said. “And we’re tired of being considered expendable.”

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines on equipment to protect against Ebola, they’re just that — guidelines –without any means of enforcement.

Deborah Burger, co-president of NNU, testified Oct. 24 before a Congressional committee asking for legislative mandates, and NNU sent a letter to President Obama requesting an executive order to force compliance with standards to protect nurses and other health-care workers.

DeMoro, who’s also executive director of the California Nurses Association, said she hoped a meeting with Gov. Jerry Brown would result in action that might serve “as an example for the nation.”

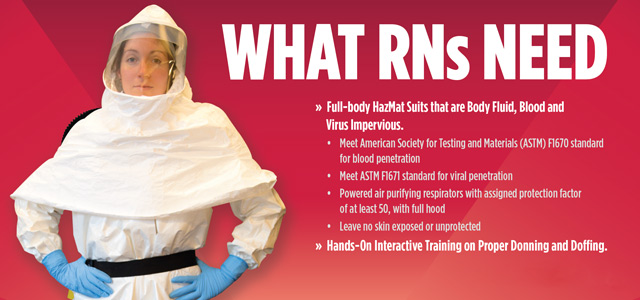

The nurses want full-body hazmat suits that meet the American Society for Testing and Materials F1670 standard for blood penetration and F1671 standard for viral penetration and that leave no skin exposed or unprotected, and they want National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health-approved powered air purifying respirators with an assigned protection factor of at least 50.

They also want training, including practice putting on and removing protective gear.

“We’re putting our lives on the line, but the hospitals are saying our lives aren’t worth it,” Roemer said. “You can’t imagine the questions from our families. One colleague’s 6-year-old asked, ‘Mommy, do you get to wear the suit that keeps you safe from bad germs?’”

Nurses have activities planned in Boston, Chicago, Houston, Las Vegas, Memphis, Miami, St. Louis and New York City; as well as Augusta, Ga.; Bar Harbor, Maine; Durham, N.C.; El Paso, Tex.; Kansas City, Mo.; Lake City, Va.; Lansing, Mich.; Massilon, Ohio; St. Paul, Minn.; and Tampa, Fla.; and the Philippines.

Two nurses contracted Ebola from caring for just one patient in a Dallas hospital in October and have been treated successfully. It doesn’t take a math genius to realize the danger not just to nurses but to the public.

“I want the public to understand we’re fighting for them, for the patients who are people at their most vulnerable,” Roemer said.

“Nurses have historically been leaders in public health issues,” DeMoro said. “Now they’re rising up again.”